First, I want to apologize for the big gap in posts. My last two weeks have been filled with travel and athletes visiting leaving little time for writing or anything else. Things are starting to settle down now so I should be able to get back into a normal routine. (I’ve got three trips coming up in the next month including one to London.) Also, I’d like to take this opportunity to again point out that I post daily to www.twitter.com/jfriel. Here I often mention what the athletes I coach are doing in training (along with my mundane thoughts :). Now back to business…

One of the athletes I coach, Seth B., spent the last four days here training, going through physical and skill assessments, testing, getting a bike fit and just talking training philosophy and direction. He’s an analytical like me and likes to dig into the details of sport training. One of our conversations was about the risks and rewards of workouts. “Risk” refers to the potential for injury, illness, burnout and other breakdowns that may occur because a workout or a closely spaced series of similar workouts is so challenging. “Reward” has to do the benefits that may result from training.

All athletes seek to improve their fitness by increasing the stress they place on their bodies. The stress can vary from very low to very high. The lowest-stress sessions are short, slow and low-effort preceded and followed by extensive rest time. High-stress workouts are just the opposite and include either long duration (relative to what the athlete’s normal duration is), high intensity or high frequency. I gave him an example of this latter from younger and dumber days nearly 30 years ago when I would run a marathon in the morning with a friend and then come home and put in 10 more miles that afternoon. Both were slow and low-effort but long duration and high frequency made them risky. I often paid the price for such “training” back then by dealing with extended down time due to injury. That’s how I first came to understand the risk-reward curve.

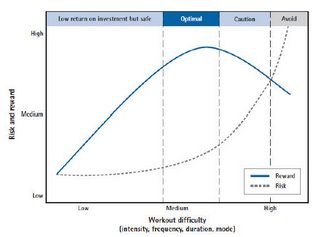

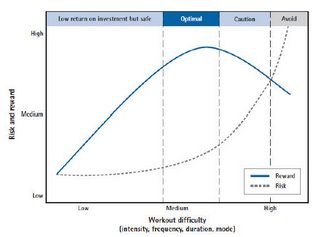

Here in this diagram you can see what I’m talking about. Change the words a bit and you might make this a guide for investing in the stock market. There it’s common knowledge that stock which has a high potential for a monetary reward is associated with a high-degree of risk. The blue chip stocks, those that have a long history of consistent growth, are generally considered low risk (things have changed though recently, haven’t they?). So as the reward of investing in stock increases, the risk also increases. The opposite is also true. You could become wealthy in a short period of time, or lose it all when “gambling” with high-risk stocks. It’s essentially the same with training.

Athletes who continually experience breakdowns because they “over-invest” in high-risk training will never achieve their potential. Those who only do low-risk workouts will also never come close to their potential. Some risk is required to succeed at the highest levels. You need to control that risk to be successful.

So what is the riskiest training? First of all, running is among the riskiest sports due primarily to the orthopedic stress (“pounding”) associated with it. Runners without a long injury history are rare. Soft but firm running surfaces (trails, grass, dirt) will moderate some of the risk of running. One of the things that also makes running risky is its eccentric contractions. In such a contraction the muscle lengthens as you attempt to shorten it. Visualize a reverse arm curl in which you slowly lower a heavy weight. The calf and quads experience this with every step while running. That’s why your quads are so sore after a marathon. Essentially, the muscle is being pulled apart. On the other hand, cycling and swimming rely primarily on “concentric” contractions, meaning the muscle gets shorter as it contracts. Visualize arm curling a heavy weight from hip high to shoulder high.

Swimming is one of the lowest-risk sports. While overuse injuries certainly occur among swimmers, mostly to the shoulder, the rate of such setbacks is low compared with runners. Poor technique, paddles and drag or resistance devices increase the risk.

The same goes for cycling where the knee is the body part most commonly injured from doing too much. Risk is increased here by, first and foremost, having a poor bike setup. And probably the most common high-risk bike setups I see have the saddle too low and too far forward. Also raising the risk for cyclists is high-gear pedaling, especially on a hill and in the seated position. Inadequate gearing (meaning not enough low gears) is often associated with knee soreness and loss of training time.

Another risky but potentially rewarding activity is plyometrics, especially the kind that includes a lot of landings at the end of downward jumps. This could be jumping over objects or off of high platforms. Jumping from the floor to land on a knee-high box has a much lower risk but also a lower reward. (Read more about plyometrics here.)

Heavy-load, low-rep weight training is also risky, but has a high potential for payoff if done correctly. Others are very high-speed sprints done much faster than is usual, hill training of any type and early season racing before fitness is well-established.

Note that I am not saying to never do moderately high-risk workouts. The key to being successful with them is to build into them gradually by starting with the lower-risk variations and gradually, over a significant amount of time, increasing the stress level. For example, with plyometrics start with upward jumps onto a platform, or low-jump-height movements such as rope jumping (which I use a lot with athletes). The key to increasing the reward while keeping risk controlled is patience. You must allow the body to adapt slowly and gradually. The more you try to force the body to adapt the greater the risk becomes.

(For more on this subject see my previous risk-reward posts here and here.)