Finding the Right Coach, Part 2

The following is Part 2 of 3 parts on finding a coach who is right for you. Realize that some of what I am telling you here is my opinion. You may well disagree with what I think are important characteristics for a coach. In that case, I hope reading this and thinking about the details gives you a clearer idea of what you want in a coach. I will post Part 3 by Friday.

PERSONAL TRAITS

Beyond the rather basic considerations in Part 1, what personal characteristics should you look for in a coach?

• Knowledge. While it’s not always necessary, having an advanced degree in a sport science can gives the coach a depth of understanding when it comes to training. But I should also say that some of the best coaches I’ve known had no formal training in the science of training. This is a plus but shouldn’t be a “must have.” Does the coach have experience teaching and refining the skills you need to improve upon? This could be swimming, mountain biking, running, cross-country skiing, or whatever your skill limiter happens to be. Realize that when it comes to teaching skills the coach should live near you.

• Experience. Has the coach helped athletes like you achieve goals like yours? Is the coach known for how successful his or her athletes have been? Or perhaps the coach is well known as a competitive athlete. I must say that I’ve known several excellent coaches who never participated in the type of event they coach, so don’t let this point blackball someone who is otherwise excellent.

• Compatibility. Personality is very important. Look for a coach who sees the world much as you do. Make sure you can communicate easily.

• Trust. You need someone with whom you can comfortably talk about the details of your life. Of course, this won't be the case immediately. But everyone I've ever coached has eventually confided in me things they would usually tell only to a relative or close friend.

• Motivation. Do you need someone to hold your feet to the fire? Or are you highly motivated and need a coach who will pull on the reins to keep you from overtraining? Is the coach a cheerleader or a task master? With which would you prefer to work?

• Style. Some coaches are scientists. They experiment, collect data, analyze the data, and adjust your program as necessary. Others are artists who ask how you felt in a workout and compare that with their experience base. From this they draw conclusions and adjust your program if needed. There are some coaches who have an interesting mix of both of these talents.

• Methodology. Are you more comfortable with one method of coaching or another? For example, there are coaches who are very good at designing programs that are high-volume-based. Others are very good at using variations in intensity to achieve goals. Is there a system of training you like or seem to respond well to? Perhaps it’s from my Training Bible, or from Chris Carmichael’s model, or Mark Allen’s. You can ask prospective coaches about such details.

INTANGIBLES

Having done this now for nearly 30 years I’ve found there are several things I’ve come to expect of coaches. These are little things that I find valuable in guiding any athlete to a higher level.

• Frequent contact. If you have signed up for unlimited contact and support from a coach you should expect frequent contact initiated by either of you. This should be at least weekly but daily is better. This could involve reviewing your daily log and commenting on things that stand out and answering your emails and phone calls in a timely manner.

• Feedback. A coach who isn’t overburdened with too many clients will often have you and your unique needs on his mind. This is really what you are buying – brain time. It should be apparent that your coach is indeed thinking about you. This is most obvious by the feedback the coach gives you. He or she should be keeping you abreast of where you are right now in your quest to achieve your goals and occasionally discuss alternative routes and suggestions for getting there.

• Support specialists. No one can know everything about everything, and yet coaches are often put in situations where they need to do just that. I’ve found that the best coaches almost always rely heavily on the guidance of specialists when facing challenging situations. These specialists could be physical therapists, sports medicine physicians, chiropractors, podiatrists, bike fitters, sports psychologists, nutritionists, and even other coaches.

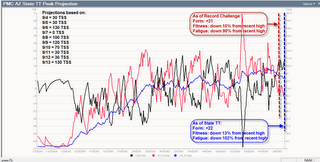

• Effective planning. I believe good coaches are always planning ahead. Knowing what you want to achieve weeks, months or even years from now should lead your coach to create a plan for getting there. Achieving long-term goals is like driving across the country: You need a map to keep you going on the most effective routes. You also need a compass to take you in the right direction. That brings us to the next point.

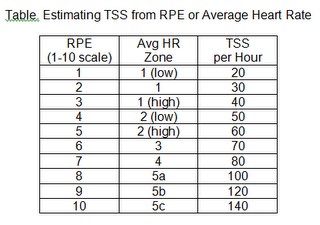

• Data driven. Good coaches typically make training decisions based on two sources – intuition and data. Be careful of coaches who make all decisions because of how they feel you need to be training. Coaches who collect and analyze training and race data are a better bet to take you where you want to go.