If you could wish for one athletic-enhancing gene it should be the one that improves your capacity to recover quickly from workouts. Athletes with this gene seem to naturally become the best athletes in their respective racing categories. There isn’t any scientific data to back this up, but there seems to be a strong correlation between one’s ability to recover and the rate of one’s fitness progression. Recovering quickly also means getting in good shape quickly.

Why is this so? There is an easy explanation: It’s during recovery following hard training that the body realizes the changes that we call “form,” which is simply to say one’s potential for performance in a race or in subsequent training. These changes may result in fat-burning enzyme increases, more resilient muscles and tendons, decreases in body fat, greater heart stroke volume, more glycogen stored in the body, and on and on. Besides overloading your body with the stresses of hard exercise, focusing on recovery is the most powerful thing you can do in training to perform at a higher level. But this is the part of the training process that most self-coached athletes get wrong. They don’t allow for enough recovery and overwhelm their bodies with stress.

Recovery may be thought of in many different ways. In terms of periodization, when you insert it in the training plan is important to your eventual success as a triathlete.

Yearly recovery. “Transition” periods are needed after “Race” periods. The purpose of these low-volume, low-intensity Transitions is to allow your body and mind to rejuvenate before starting back into another period of hard training. So that if you have two A-priority races in a season you should also generally have two Transition periods. The first Transition may only be three to five days, but the one that comes at the end of the season may well last four weeks or even longer depending on how challenging the previous season, and especially the final part, was.

Monthly recovery. Build recovery into your monthly training plan every third or fourth week. This regular period of reduced workload may be three to seven days depending on what you did in the previous hard training weeks, how fit you are becoming and other individual factors.

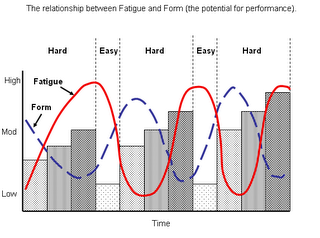

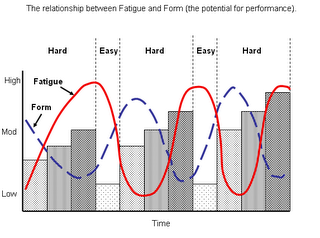

The accompanying figure illustrates what happens when you do this. As your fatigue increases over the course of two to three weeks of increasing workloads, your form diminishes. Form is your potential for performance. In other words, how well you may train or race at any given point in time. Notice that fatigue and form follow nearly opposite paths, but that form lags behind the changes in fatigue. It takes a few days of reducing fatigue to produce increases in form. A key principle of training is to unload fatigue frequently which has the effect of improving your readiness to train well again. Without unloading fatigue you become a zombie doing workouts with low quality and no enthusiasm.

Weekly recovery. Within each week there should be hard and easy days. No one, not even elite athletes, can train hard every day with no recovery breaks. Easy days are as necessary for fitness and form as sleeping at night is for health and well-being. Some athletes need a day completely off from exercise every week. Other athletes, especially those with the quick-recovery gene who also have a high capacity for work, can exercise seven days a week. These elite athletes will still need easy days, however. “Easy” days are relative to the individual. There is no standard that every athlete must abide by. That said, it is important even for high-capacity athletes to occasionally have days completely off from exercise.

Daily recovery. Multiple daily workouts are especially challenging. When doing two-a-day workouts there will be times when both are challenging sessions, but there will also be days when both are light workouts or one is hard and one is easy. This is what makes any sport, but especially triathlon, so complex and why having a coach is often necessary to achieve high levels of success.

How often you insert recovery in your training program; how long this period of recovery lasts; and what exactly recovery means to you in terms of workout duration, intensity and frequency is an individual matter. The only sure way for you to determine each of these is through trial and error. Some athletes will find they can recover quite nicely on short periods of infrequent recovery. Others will discover they need frequent long periods to recover adequately.

Be aware that the need for recovery is a moving target and is always changing as the total stress in your life and how fit you are changes. Be conservative when trying different recovery programs. “Conservative” in this case means erring on the side of too much recovery.

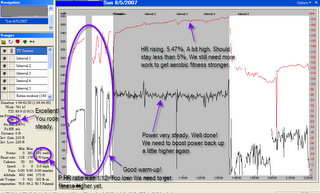

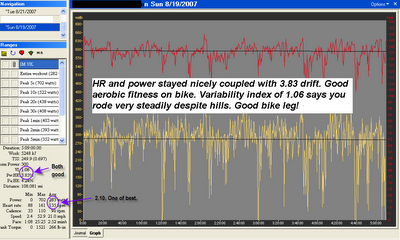

The power graph you see above was produced by one of the athletes I coach--Eric VanMoorlehem. It is from Ironman UK on August 19. Eric races in the 35-39 age group. He had a difficult preparation for IMUK due to a nagging Achilles tendon inflammation which stayed with him most of the summer. Because of this he didn't run much. He also felt the bike aggravated the Achilles (he has switched over to a midsole cleat position since the race to take the load off of his Achilles and calf). So he was a bit limited on training there also. So he went in to the race with both of us concerned that he may not qualify for Hawaii which he had done each of the last two seasons. There were three IM slots in his age group and we couldn't count on a roll down so we felt he had to get 3rd.

The power graph you see above was produced by one of the athletes I coach--Eric VanMoorlehem. It is from Ironman UK on August 19. Eric races in the 35-39 age group. He had a difficult preparation for IMUK due to a nagging Achilles tendon inflammation which stayed with him most of the summer. Because of this he didn't run much. He also felt the bike aggravated the Achilles (he has switched over to a midsole cleat position since the race to take the load off of his Achilles and calf). So he was a bit limited on training there also. So he went in to the race with both of us concerned that he may not qualify for Hawaii which he had done each of the last two seasons. There were three IM slots in his age group and we couldn't count on a roll down so we felt he had to get 3rd.